HELL JOURNEYS

Unpublished data has revealed shocking new evidence about a secretive global trade in livestock, raising concerns about animal welfare and disease spread.

It’s just after midnight at a factory farm in South Jutland, Denmark, and 170 pigs are being loaded onto a waiting transport lorry. The animals are beginning a two day journey that will take them halfway around the world, starting with an overland trip down to the German border, before travelling the length of the country and exiting into Luxembourg.

From there the consignment heads to the international airport, where the pigs are unloaded and transferred onto a jet that will fly them more than 10,000 kilometres to Cambodia. The animals are then disembarked and loaded onto another truck that takes them - finally - to a facility somewhere south of the capital Phnom Penh. Danish pigs are prized as breeding stock internationally. These animals have been bought by a global agribusiness that operates industrial farms across Asia.

In eastern France, in the La Chevillotte region not far from the Swiss border, 31 cattle are taken from a farm to begin a journey that will see them in transit for more than a week - eight days and 20 hours - as they are driven, via Poland and the former USSR, to their eventual destination in Uzbekistan. The central Asian country is a regular importer of EU cattle.

In Northern Ireland, in the UK, at an assembly centre (facilities where livestock destined for export are collected together) more than 350 sheep are starting what will be their final journey. They are loaded up, then trucked then shipped then trucked again - via Dublin port in Eire and Cherbourg on France’s channel coast - to the Occitanie region in the south of the country. After a journey lasting almost three days, the sheep arrive at an abattoir where they will be slaughtered and processed.

All three of these cases are detailed in a cache of previously unpublished records that have revealed startling new evidence about the EU’s role in the controversial “long distance” trade in farm animals.

The documents, copies of official planning records known as animal journey logs, reveal - for the first time - granular details of planned and completed journeys of more than 180,000 consignments of EU cattle, pigs, sheep and other species over a 19 month period between 2021 and 2023. They show how millions of livestock were trucked, shipped and flown both within Europe and globally on lengthy journeys lasting eight hours or more, with many spanning days or even weeks.

Campaigners have long criticised such transports, citing overcrowding, exhaustion, dehydration and stress as key factors affecting livestock health and welfare. The movements have also raised concerns over the spread of disease, particularly the health implications of transporting any livestock contaminated with antibiotic resistant infections.

Scrutiny

The findings, part of a wider dossier of evidence published today by the pressure groups Compassion In World Farming (CIWF)and Eurogroup For Animals (EFA), come as EU officials prepare to announce new proposals for amending regulations relating to the trade.

The issue has been the subject of intense scrutiny in recent years, with a number of official reviews, as well as sustained lobbying by both animal campaigners and livestock interest groups. A number of countries - including the UK, Brazil, Australia and New Zealand - have already committed to tighter regulation on live animal exports.

The livestock industry defends the trade on economic grounds, maintaining that the movements are simply responding to demand. They also say welfare remains a priority, as it only makes commercial sense to export healthy animals, pointing out that some factors - such as increasing distances to slaughterhouses - are beyond their control.

Advocates also argue that the EU has some of the strictest regulations in the world around animal health, welfare and food safety, and that transport conditions have improved in recent years thanks to new equipment, technology and enforcement.

Yet in a final salvo fired ahead of the EU’s expected announcements, the report calls for an embargo on EU farm animals being exported outside the bloc, strict limits to be placed on journey times between EU nations, and the outlawing of the transport of unweaned livestock.

Background image: Martina Zamudio / We Animals Media

Peter Stevenson, an expert on the trade at CIWF and the report’s lead author said that “although we knew that millions of animals were enduring cruel and unnecessary journeys in the name of profit, this research shows that the situation is far worse than we had feared. The EU must address this as a matter of urgency.”

Anja Hazekamp, a Dutch MEP, said she was shocked at the findings. “It is unsustainable to keep as many animals as we do in the European Union. We cause a lot of problems for animal welfare, climate, biodiversity and for human health”, she said. “We need to eliminate long distance transport, rather than transporting animals all over Europe and to the other side of the world. It is ridiculous that animals are sent as far as Brazil and Colombia.”

Transnational trade

Reineke Hameleers, CEO of EFA, called for a transition towards a trade in meat and carcasses, rather than live animals, saying the "transnational nature of live exports makes it challenging to protect the welfare of animals.”

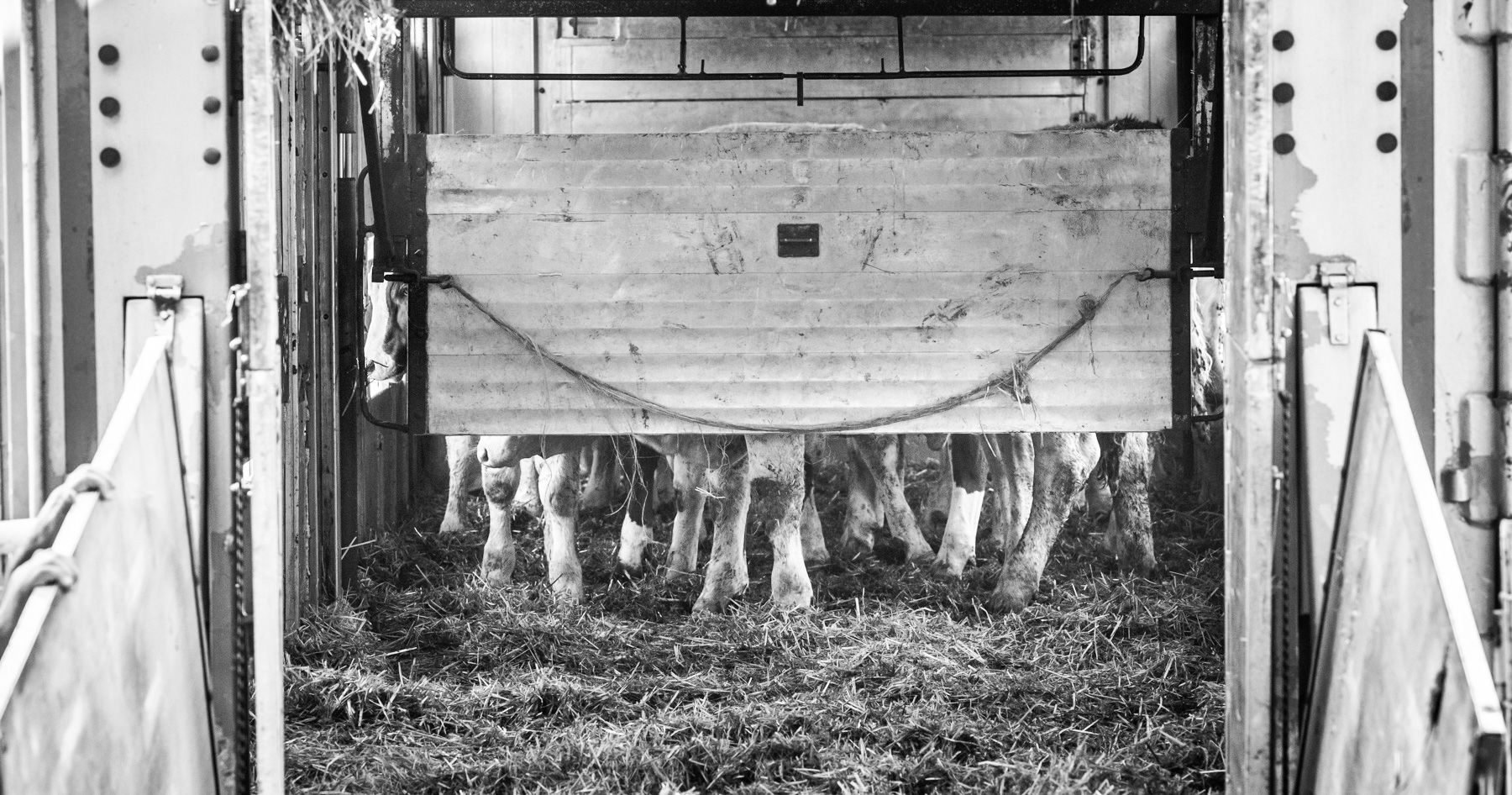

Pigs are amongst the most commonly transported animals within Europe.Jo-Anne McArthur / We Animals Media

Pigs are amongst the most commonly transported animals within Europe. Jo-Anne McArthur / We Animals Media

Responding to the findings, a spokesperson for the European Commission said that it had been working to improve animal welfare for over 40 years, "progressively improving the lives of animals and adopting welfare standards in legislation that are amongst the highest in the world."

"Animal welfare is and will remain a priority for the Commission. An example is the adoption in early 2023 of new rules on the transport of animals by sea. The Farm to Fork Strategy foresees a revision of the EU’s animal welfare legislation. This preparatory work is ongoing, covering legislation for the welfare of animals at farm level, during transport, at the time of killing and to establish a voluntary European label for animal welfare."

The spokesperson said that the proposal on the protection of animals during transport, one of the four legs of the legislation, is the most advanced and will be presented in December 2023.

***

Researchers used journey logs - generated by farms and animal transport companies - publicly available trade figures, Freedom of Information responses, satellite mapping and maritime data to compile one of the most comprehensive overviews to date of the EU's livestock trade.

They found that 44 million farm animals annually were transported between EU member States and exported internationally, many of them long distance journeys lasting 8 hours or more.

Overall, these lengthy transportations represent a small but significant number of the 1.6 billion live animals (many of them chickens) that are believed to be moved within the EU and internationally each year as part of meat and dairy supply chains. Globally, some estimates have suggested that as many as 5 million farm animals are in transit on any given day, although precise numbers are difficult to pinpoint owing to a lack of centralised data.

Rising demand

The trade exists because of rising demand for meat in large parts of the world, with European companies cashing in on the need for stocking farms with both breeding and fattening animals. For some countries - including Spain, Denmark, Ireland and Romania - the export of livestock is a key component of their farming economies.

The closure of abattoirs and consolidation within the meat processing sector has fuelled longer transports in some regions. In fact, records suggest that as many as 3 million EU farm animals were reared in one country before being trucked across at least one border for slaughter. Some of these livestock were processed by meat companies that supply European supermarket chains, implicating a number of well known brands in the controversy.

In other cases, EU livestock are used to “seed” factory farms elsewhere in the world, campaigners say, with breeding animals being supplied to agribusinesses linked to environmental harms, such as water pollution, and conflicts over the spread of US-style “mega farms”.

The investigation revealed exports to multiple international destinations, including Brazil, Belarus, Thailand, Cambodia, India, Iran, Colombia, Mexico, Cameroon, Kazakhstan, Senegal, Vietnam, South Korea, the Philippines, Libya, Russia, Egypt and Turkey.

Background image: Havva Zorlu / We Animals Media

Some of the longest overland journeys - such as the transport of thousands of cattle and sheep by road to Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia - were found to last up to three weeks.

Many animals are transported by boat, the report says, with 63% of livestock exported out of the EU found to be travelling by sea. In the 19 month period documented in the report, 217,000 sheep were transported from Spain to Saudi Arabia on journeys taking up to 18 days.

Fatalities

Such journeys can often involve poor conditions and animal fatalities. In 2019, 14,000 sheep drowned in the Black Sea when a ship transporting them from Romania to Saudi Arabia capsized. Even before boarding, campaigners say, animals are often held at ports for extended periods in stationary and unventilated trucks, subjecting animals to heat stress.

EU regulation necessitates animals receive a welfare check at ports to ensure they are healthy enough to continue their journeys. Yet campaigners cite a European Commission report which recently found that “in many cases [records of these checks are] poor or do not exist.”

The biggest livestock boats can transport as many as 18,000 cattle or 75,000 sheep, yet it’s alleged that on board some vessels there are no crew members responsible for welfare, meaning diseased or injured animals can go untreated.

Overcrowding on animal transports can lead to injuries and the spread of disease. Jo-Anne McArthur / We Animals Media

Overcrowding on animal transports can lead to injuries and the spread of disease. Jo-Anne McArthur / We Animals Media

The new records also show how some live animals - mainly pigs - have been transported by air to countries as far afield as Thailand, the Philippines, Singapore, Vietnam and Cambodia. Others were flown to destinations in Africa, including Cameroon, Ghana and Uganda.

Many of the journeys cited involve unweaned, infant calves and lambs. Over 300,000 unweaned calves were estimated to have been transported between EU member states each year between 2019 and 2021. “Most of these calves are the unwanted male calves from the dairy sector. These tiny animals, often just two to three weeks of age, are frail and quite unsuited for transport,” the authors note.

Hunger and thirst

“They do not yet eat solid food. They depend for nutrition on milk or milk replacer (powdered milk mixed with water). However, it is not possible to give calves milk replacer while they are on board a truck. And so they are driven on long journeys without feed and often without water, resulting in hunger, thirst and increased vulnerability to disease.”

EU regulations currently allow unweaned calves to be transported on journeys of over 8 hours once they are 14 days old.

Road transport is a commonly used method for moving farm animals in Europe. Lukas Vincour / Zvířata Nejíme / We Animals Media

Road transport is a commonly used method for moving farm animals in Europe. Lukas Vincour / Zvířata Nejíme / We Animals Media

Campaigners say injuries can occur during transport. Louise Jorgensen / Animal Sentience Project / We Animals Media

Campaigners say fatalities and injuries can occur during transport. Louise Jorgensen / Animal Sentience Project / We Animals Media

Critics are calling for strict new rules to curtail the trade in live animals. Lukas Vincour / Zvířata Nejíme / We Animals Media

Campaigners are calling for strict new rules to curtail the trade in live animals. Lukas Vincour / Zvířata Nejíme / We Animals Media

The report also alleges the inaccurate recording of some transport times, with many journeys taking longer than officially stated. 60% of the journeys recorded in the logs started from assembly centres. These are sites where animals from different farms are unloaded and held ready to be reassigned to trucks for the next part of their journeys.

One of the alleged “tricks of the trade”, say researchers, sees transport organisers record assembly centres as the original point of departure, despite animals having already been in transit from farms. This means the operators could be extending the legal permitted travelling time.

EU regulation stipulates a resting period of at least 48 hours at an animal’s place of departure before journeys can begin. However, at assembly centres, the time required is only 6 hours. This means animals can be transported for hours before reaching assembly centres, only to be quickly transported again.

***

Some vessels carrying livestock have sunk in recent years, leading to animals drowning. Jo-Anne McArthur / Israel Against Live Shipments

Some vessels carrying livestock have sunk in recent years, leading to animals drowning. Jo-Anne McArthur / Israel Against Live Shipments

It is not just welfare that’s compromised by the controversial trade. Experts have warned of the potential spread of antibiotic resistant “superbugs” as contaminated livestock are trucked, shipped and flown across Europe and internationally.

Antibiotics are used on farms both to treat disease and - until recently, with the introduction of tougher EU regulations - preventatively to stop pathogens spreading. Poor livestock management and housing conditions, close proximity of animals and stress, often associated with intensive livestock production, can lead to an increased spread of disease and higher use of antibiotics.

Superbugs

Antibiotic resistance occurs when bacteria are repeatedly exposed to antibiotics: the continual exposure causes them to evolve and develop resistance to drugs that would otherwise kill them. When these drugs no longer work, it can render doctors (and vets) powerless or severely hamper their ability to treat previously treatable illnesses — in humans and animals.

Around the world, an estimated 700,000 people now die each year from infections caused by bacteria that have become immune to antibiotic treatments. A UK Government review predicted that by 2050 this number could rise to 10 million deaths a year, costing the global economy $100 trillion.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has warned that the planet risks entering a “post antibiotic era” where previously routine medical procedures become deadly. Lifesaving operations — organ transplants, cancer treatments, caesarean sections — will become much more risky.

Although overuse of antibiotics in human healthcare is the primary driver of the crisis, usage on farms is a significant factor, with at least half of all antibiotics globally now fed to animals.

Particular problems from the veterinary use of antibiotics arise when the same, or similar, drugs used in human healthcare are used in livestock production. This can directly result in the antibiotics becoming ineffective when used to treat human illnesses — chiefly serious food poisoning cases — which are transmitted from farm animals to people via the food chain.

Disease transmission

The use on farms of antibiotics classified as “critically important to human health” has been a key focus of reduction drives in recent years.

When livestock are transported, animals contaminated with drug-resistant infections can easily transmit the illnesses to other healthy animals travelling in the same consignment.

Dr Gertraud Schüpbach, head of the Veterinary Public Health Institute at the University of Bern, said there were two main issues: “The first is direct transport of resistant bacteria [via contaminated animals], the second is that if you mix animals from different origins and transport them over a period of time they are much more likely to contract all kinds of disease.”

Dr Annemarie Käsbohrer, from the National Reference Laboratory for Antimicrobial Resistance at the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment said that when animals are stressed they excrete pathogens, increasing risk for other animals. “If animals are stressed it is easier for pathogens to infect them” she said.“If the immune system is weakened by any type of stress then these bacteria and viruses can multiply more.”

Despite raising concerns, the academics noted a lack of evidence around the issue and called for further research.

Background image: Jo-Anne McArthur / Israel Against Live Shipments / We Animals Media

Last year, a scientific assessment into the issue published by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) identified that “long journeys that require rests in assembly centres and control posts are associated with higher risks, due to specific factors such as close contacts with animals from different farms, environmental contamination and stress.”

The assessment also found that “minimising transport duration” and thoroughly cleaning vehicles, equipment and spaces where animals are loaded and unloaded were “some of the measures considered effective in reducing the transmission of resistant bacteria during animal transport.”

A spokesperson for EFSA said: "EFSA’s findings help to identify measures to reduce the spread of antimicrobial resistance, as well as unnecessary pain, distress and suffering for animals during transport. It’s important to note that the planning, implementation and evaluation of any potential action taken to protect consumers, animals and the environment is in the hands of the legislators."

Livestock vessels can hold thousands of animals. Gav Wheatley / HIDDEN / We Animals Media

Livestock vessels can hold thousands of animals. Gav Wheatley / HIDDEN / We Animals Media

Some cattle spend up to three weeks in transit. Louise Jorgensen / Animal Sentience Project / We Animals Media

Some cattle spend up to three weeks in transit. Louise Jorgensen / Animal Sentience Project / We Animals Media

Millions of animals are exported direct to slaughter. Jo-Anne McArthur / Animal Equality / We Animals Media

Millions of animals are exported direct to slaughter. Jo-Anne McArthur / Animal Equality / We Animals Media

Pigs are sometimes flown globally for breeding purposes. Andrew Skowron / We Animals Media

Pigs are sometimes flown globally for breeding purposes. Andrew Skowron / We Animals Media

Cattle tags. Despite each animal movement being recorded, public data on livestock destinations is scarce. Jo-Anne McArther / We Animals Media

Cattle tags. Despite each animal movement being recorded, public data on livestock destinations is scarce. Jo-Anne McArther / We Animals Media

Some major EU exporters of livestock are known to be hotspots for antibiotic resistant diseases. In Denmark, a key exporter of pigs, almost 90% of the country’s pig herds are now thought to be contaminated with livestock variants of the superbug MRSA. An investigation previously highlighted how breeding animals from Danish farms known to be contaminated were free to be exported owing to regulatory loopholes.

In Spain, official data shows that large numbers of pigs are infected with salmonella, and that as many as 30% of these may carry drug-resistant strains.

Increased use

Other nations involved in the trade in live farm animals have recorded sharp increases in veterinary usage of some “critically important” antibiotics in recent years, including Poland, Romania, Portugal and Greece.

Some experts say that longer livestock transport journeys can themselves increase the need for treatment with antibiotics. “Animals, even if they are domesticated, are not built for standing still, which they have to do in long haul transport. That will cause health problems, and then you need to treat them,” Professor Sternberg Lewerin, Professor in Epizootiology & Disease Control at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, said.

She said that increasing use of antibiotics remains part of the problem: “We’re trying to fix the effect of transporting and moving animals around instead of trying to reduce the moving around.”

Header image: Jo-Anne McArthur / We Animals Media. All images reproduced from We Animals Media international reportage project on live animal transport.